5 Keys to Rapid User Research

As designers and problem solvers, we know the importance of research to build deeper empathy with audiences, as it enables us to witness experiences from their perspective. Research reveals opportunities and inspires design ideas, and it can help us evaluate the effectiveness of our solutions. It can also help align teams around shared goals.

But when projects run on tight deadlines and budgets, incorporating user research can seem challenging. So what are some lightweight, nimble ways to approach evaluative research? Recently, we had the opportunity to lead a fast-paced project for the California Academy of Sciences, and needed to come up with creative approaches.

Cal Academy asked Hot Studio to conduct a user study with a rough cut of its Earthquake planetarium show. The overall goal was to evaluate how well viewers could understand the geology content in the show, such as the causes of earthquakes. Our research would be used to recommend any potential adjustments to the film’s narration and visuals.

We were thrilled about the prospect of working on this project—and intrigued by its challenges. How would we recruit and interview a large number of participants with our tiny project team? How might we collect quantitative data to support qualitative interview data? And finally, how might we design the research activities to foster rich conversations about specific sequences of the film, without interrupting the film’s playback?

These challenges pushed our team to be resourceful, organized, and creative. Here are some of the keys to our approach:

- Start with the end in mind

- Take an iterative approach

- Create activities, props, and tools (as well as great questions)

- Enlist colleagues or clients as assistants

- Leverage tools wisely

1. Start with the end in mind

The first step for any research project is to clarify your goals. What questions do you need the research to answer? Which hypotheses do you need to validate? Then craft your approach to the research accordingly. Clearly articulated objectives will give you the focus you need to select research methods and activities, ask the right questions, and frame your results. For rapid user research, focus on the top few questions you need to answer in order to proceed to the next step of your project.

For the Cal Academy project, the high-level goals were to evaluate how well viewers could follow the geology content, and to recommend potential tweaks to the film. By sitting down with the filmmakers, we clarified which specific aspects of the geology content were most important, and which sequences of the film were potentially unclear. We discussed what could be easily modified (like narration) in the event that we wanted to recommend changes. Based on our goals and meetings with the Cal Academy team, we made a list of research objectives. And with clear research objectives in mind, we were well-equipped to plan our approach and activities, and start crafting an interview guide.

2. Take an iterative approach

When planning research, take an iterative approach so you can learn from your experiences and adjust as you go. So what does this look like? Rather than scheduling all your research in one contiguous block, break it up into a series of sessions and intervals. Build in enough time between sessions to review your findings and, if appropriate, revise your activities and materials.

For this project, we decided the best approach would be to conduct a series of special screenings of the show. After each screening we interviewed viewers about their experience. A pilot screening helped us to spot oversights in logistics—like the fact that we needed someone to act as a “traffic cop” and direct participants after the show. In the intervals between screenings, we synthesized and discussed our initial findings, which included specific recommendations for refinements to the film’s narration script.

Based on these recommendations, the Cal Academy filmmakers swiftly re-recorded the narration—giving our team the opportunity to evaluate the new version at the next screening. It was agile filmmaking at its best!

3. Create activities, props, and tools (as well as great questions)

Many people think good research hinges on conducting interviews. But in fact, good research isn’t always about conducting verbal question-and-answer interviews with people—there’s much more to it. Based on the goals and objectives you identified for the research, consider various types of participant activities, as well as props or tools, you can design to produce insights instead of solely focusing on the interview process.

For software usability studies, we usually observe participants individually as they interact with a product to complete specific tasks. But for this Earthquake project, there was no explicit interaction; we couldn’t observe participant understanding directly.

In this case, the challenge was how to gauge understanding without interrupting the film—and how to do so with a large number of participants. To address this, we came up with a two-fold approach:

1. Find a scalable way to collect quantitative info in real time during the film

2. Interview participants about their experience after the film

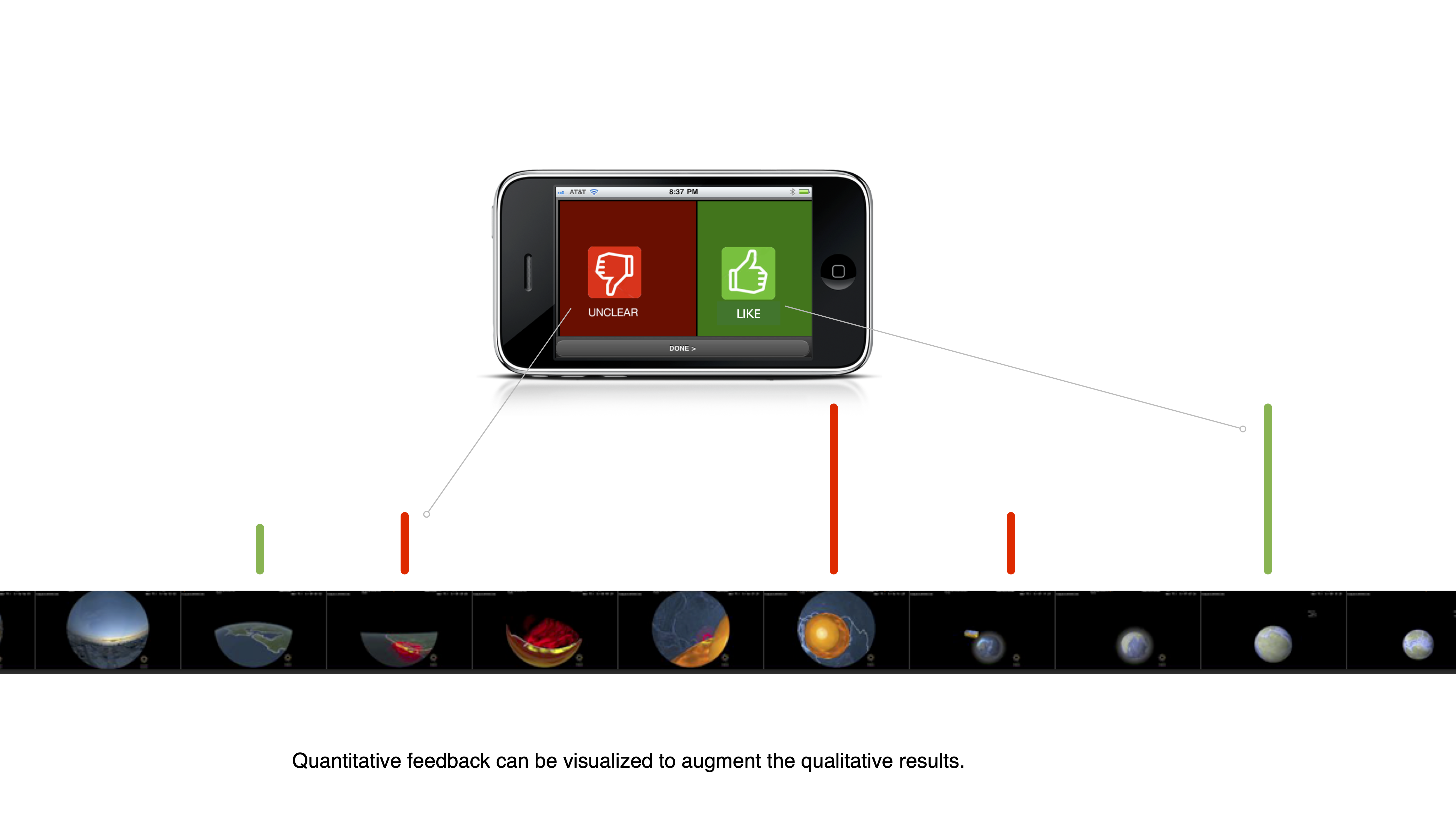

We created an easy to use mobile web app that participants could use while watching the film to log moments they thought were “unclear” or “clear.”

Participants ran the app from their own cell phones to submit feedback. Our team aggregated and graphed the results to identify key points in the film which were unclear.

A mobile web app enabled participants to submit real-time feedback. The data tells a story and can be mapped to show important moments in this film sequence.

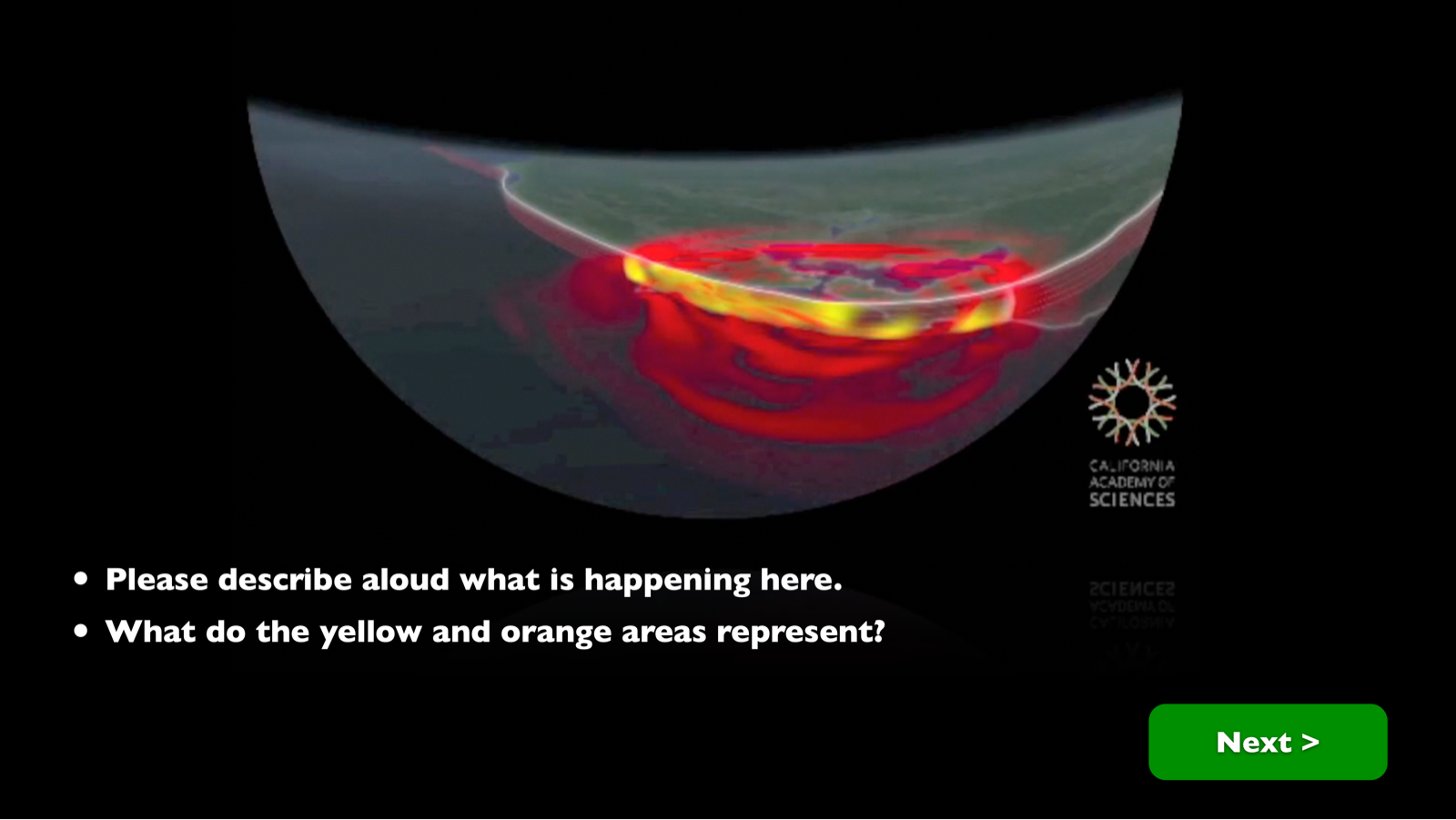

After the screening, we interviewed participants about their experience. Rather than having a strictly verbal conversation, we created video clips of key sequences in the film, and set them up so that participants could view and control them on a laptop. These visual props facilitated very rich and efficient conversations—and proved helpful with people not fluent in English—much more so than if we only had verbal conversations.

Users could view and control video clips on a laptop during their interviews. This supported rich, clear, and efficient feedback on the film.

4. Enlist colleagues or clients as assistants

Depending on the nature of your research, you may be able to enlist the help of other designers or team members to help with certain tasks. For rapid projects, consider whether there are people who can help you record notes or transcribe recorded interviews. Are there people who can help you set up or manage sessions? Are there researchers or designers from other teams in your organization who may be able to support you for an hour or two?

For the Cal Academy project, our small staff needed to interview dozens of participants simultaneously. We put out a call to the experienced designers at Hot Studio, seeking volunteers to help with the project, and succeeded in recruiting several takers. We had help with managing sessions, note-taking, transcribing, and even interviewing. We organized an orientation session to walk through the interview guide we created, did a mock interview, and reviewed best practices for interviewing.

5. Leverage tools wisely

To give you the bandwidth to scale your research, or to focus on certain aspects of the research, consider ways technology and tools can support you in the collection and organization of your data. For rapid research projects, tools can make a huge difference.

We created a centralized repository for interview data using Google Docs. The simple fact that everyone could update the findings simultaneously streamlined our process considerably.

Another challenge on the Cal Academy project was accommodating overflow participants at our screenings. Even with our extended volunteer team, we had more participants than we could interview simultaneously—and some would simply leave instead of waiting until we were free to interview them.

Once we realized this, we used off-the-shelf tools to quickly create “self-serve kiosk” stations which enabled overflow participants to verbally record their feedback on the show. Although the data from these self-serve sessions wasn’t as rich as that from our face-to-face interviews, we were still able to get extremely valuable information.

Self-serve kiosks enabled overflow participants to record their feedback.

Conclusion

Because we took the approach described here, we successfully collected rich feedback from 60 participants, made two rounds of revisions to the film, and validated the changes—all in just two weeks. In the process, we also helped Cal Academy build more empathy for—and a deeper understanding of—the audiences they serve.

We started with the end in mind, took an iterative approach, created activities and props for our interviews, got support from colleagues, and leveraged off-the-shelf tools. We measured both quantitative and qualitative improvements to the clarity of the geology content. We also laid the groundwork for a final round of research to be conducted with the completed film. The Cal Academy team now has a much better understanding of how to approach and advance a concept with potential audiences.

I hope you find these research tips helpful in your own projects.

I’m Dave Eresian. I lead design teams that create compelling products, while championing a culture of teamwork, continuous learning, and quick iteration.

Please feel free to get in touch.